125 years and still going strong

Photo of rainbow over the Vatican. Tomas1111/Fotosearch

Few magazines are blessed to complete 125 years of publication. Thanks to you, our loyal readers, we will begin our 126th year next month. A short look back at our changing Church, government, society, and culture seems in order.

In order to serve its subscribers well, St. Anthony Messenger has grown as the Church, US government, and US culture have changed since 1893.

1893–1918: Getting Started

When St. Anthony’s Messenger began in June 1893, immigration to the United States had already largely shifted from northern Europe to Italy and the countries of central and eastern Europe. Many of these and earlier immigrants were Catholics who tended to settle in urban areas and earned their living through blue-collar jobs in factories; many others worked in sales and government service. Our magazine concentrated on promoting the message of St. Francis of Assisi (especially through the Third Order of St. Francis, now known as the Secular Franciscan Order), strong family life, and good citizenship.

In the first issue, founding editor Father Ambrose Sanning wrote that our 40-page magazine “is a herald of peace,” brandishing neither sword nor pistol like a Communist or Anarchist bomb thrower. The magazine aimed to help its readers become heralds of peace wherever they lived or worked.

St. Anthony Messenger magazine covers: June 1893 and April 2018

The magazine, he explained, does not advocate revolution, slaughter, or pillage but is conservative, announcing “heaven’s best boon—peace.” Father Ambrose set the publication’s tone by quoting the proverb, “In all things, charity.”

In 1893, he also edited St. Franziskus Bote (a devotional magazine begun in 1892 and similar to St. Anthony Messenger) and served as rector of the Cincinnati friars’ high school seminary.

In our first 25 years, the Church lowered the age of first Communion to 7; many Catholics then received holy Communion only four times a year. Around the same time, the Catholic Church in the United States began exporting missionaries instead of importing them, even as it built many new churches, schools, orphanages, and other works of charity to address the needs of newly arrived and longer-established Catholics in this country.

The United States changed considerably within the same 25 years. As a result of the Spanish-American War, it acquired the Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam—all territories with significant Catholic populations. Partly because the Holy See did not officially recognize the Republic of Italy, the loyalties of foreign-born and US-born Catholics were suspect in the eyes of many US citizens whose ancestors had immigrated to this country decades earlier. During World War I, Catholics joined the military at rates slightly higher than their percentage in the general population. US Catholics were proud to be US citizens.

By 1918, St. Anthony Messenger was using photos with its essays and international news. “The Wise Man’s Corner” column for answering questions began in 1915. The ’s in our title ceased in June 1917. Subscriptions to the magazine were sold door-to-door and through Catholic parishes. Its sister magazine, St. Franziskus Bote, ceased publication after the United States entered World War I. Anti-German sentiment caused the street in front of our headquarters to be changed from Bremen Strasse to Republic Street.

1918–43: Immigrant Church

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Catholic bishops formed the National Catholic War Council to show that Catholics fully supported this war. The Knights of Columbus set up recreation centers open to military men and women of all faiths. Catholic chaplains were recruited. After the war ended, the US bishops felt that the benefits of working together should be extended in a time of peace, deciding to hold annual meetings and to set up a national office in Washington, DC.

More Catholic churches and schools were built; men’s and women’s Catholic colleges and universities increased. Catholics gradually began moving into the country’s middle class. For many people, the Catholicism of Al Smith, the Democratic nominee for president in 1928, raised old fears that Catholics were not completely loyal to this country’s form of government. The worldwide Church did not encourage the separation of Church and state.

More Catholic churches and schools were built; men’s and women’s Catholic colleges and universities increased. Catholics gradually began moving into the country’s middle class. For many people, the Catholicism of Al Smith, the Democratic nominee for president in 1928, raised old fears that Catholics were not completely loyal to this country’s form of government. The worldwide Church did not encourage the separation of Church and state.

The first US quotas on immigrants from Europe began in 1924, using statistics from the 1890 census, when the percentages from Ireland, France, Germany, and Austria were much higher. The Ku Klux Klan reached the height of its political power nationwide, targeting not only African Americans but also Catholics and Jews. Anticlerical governments in Mexico drew protests from US Catholics, who also tended to support General Franco and the Nationalists in Spain’s civil war (1936–39). Franco was aided by the Nazis and Italy’s Fascists but opposed Communists. The US entry into World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, again prompted Catholics to organize and to show their patriotism. Catholic priests readily volunteered to serve as chaplains.

The number of people directly involved in US agriculture fell considerably in these years, and increasing numbers of people sought jobs in cities. Large numbers of African Americans moved from the South to the North, revealing racial prejudice across the country. In a sense, radio shrank the country and allowed for a direct communication previously impossible.

Labor unions grew in membership and influence, raising concerns about Communist influence within them. St. Anthony Messenger worked to explain Catholic social justice teaching as much more beneficial than Communism or Socialism for working men and women of all faiths and no faith.

By St. Anthony Messenger’s 50th anniversary issue, the magazine had increased to its present size and had started using cover color photos (on religious and family themes). In April 1943, we published “Grow Your Own Victory Garden.” Special columns for Third Order Franciscans, cooks, young people, and inquiring Catholics had begun. Ads for dress patterns had begun to appear in its pages. In the June 1942 issue, 16 writers (10 of them women) were identified as regular contributors.

1943–68: Developing a New Normal

US Catholics supported their country during World War II and did their part in helping to rebuild war-ravaged Europe. The American Bishops’ Overseas Appeal was generously supported. Most US Catholics approved the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki because of projections about lives saved among the US military personnel if an invasion of Japan had been necessary to end the war.

President Harry S. Truman, who served as a captain in World War I, was determined that World War II veterans would be treated better by the federal government than he and his fellow soldiers had been after World War I. Various GI bills created tremendous new opportunities for education and home ownership.

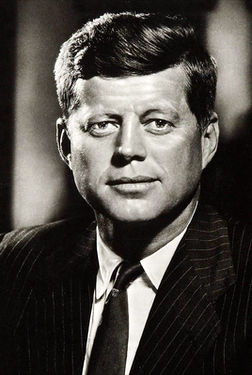

President John F. Kennedy

photo: Warren Commission US Government

That influence was felt among all parts of US society, including Catholics. This legislation and the education many Catholics received in parish grade schools were major factors in Catholic movement into the country’s middle class and into white-collar jobs. Many Catholics and others saw the 1960 election of John F. Kennedy as proving that Catholics had finally arrived in the mainstream of US society.

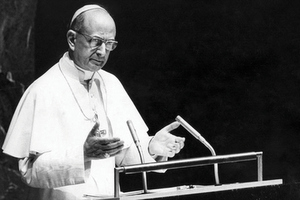

Immigration from Asia, Mexico, and Central and South America increased considerably during these years, changing the demographics of the United States and of the Catholic Church here. Ecumenical and interfaith initiatives took on a new urgency. Pope Paul VI visited New York City and spoke at the United Nations on October 4, 1965, almost two months before Vatican II concluded its fourth and final session. Television made our world smaller, giving us access to people and events we would otherwise never have encountered.

The US Catholics best prepared for the changes initiated by Vatican II were the very few who had a strong interest in the growing liturgical, social justice, and biblical movements. A Church that had prided itself for 400 years on accepting very little change now faced an entirely “new normal.” The Catholic Church’s suspicion that democracy undermined religious fervor gave way to a feeling that an amicable Church and state separation on an international scale was needed to protect religious liberty.

Pope Paul VI addresses the United Nations on October 4, 1965. Photo: CNS,Utaka Nagata

Vatican II’s “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World” reminded Catholics of their duties to their earthly city as well as to their heavenly one (#43).

Religious sisters expanded their ministries beyond schools and hospitals, becoming more frequent participants in marches and initiatives for social justice.

Many Catholics who initially supported US involvement in the Vietnam War as a way to resist the spread of Communism eventually began to have their doubts about that support. The number of Catholic conscientious objectors grew significantly. By 1968, many Catholic colleges and universities had already gone coed or would soon do so. Women became more prominent in national politics. Increasing numbers of women were elected or appointed to office on local, state, and national levels.

St. Anthony Messenger introduced a major redesign with its November 1964 issue, offering more photos selected by a full-time art director. Each issue now included editorials, letters to the editor, movie and TV reviews, a roundup of national and international news, cartoons, book reviews, and a “Words to Remember” page (a striking photo or graphic and a related quote). “Abigail, Senator McCarthy’s Better Half” appeared in our May 1968 issue. “Pete and Repeat” had been a regular feature since the July 1959 issue. By the end of 1968, the editorial team included a layman; women editors soon followed.

1968–93: Is It the Same Church?

The year 1968 saw massive social and political changes in the United States, especially on college campuses. The country became more diverse demographically and slowly began to admit that racism represents a serious moral challenge for all US citizens.

Initiatives begun by Vatican II continued to be implemented. Soon this country would have the largest number of permanent deacons worldwide. More laywomen began working on parish staffs and in the management of Catholic hospitals and other institutions—and serving as lay missionaries inside and outside the United States.

The June 1968 publication of “Humanae Vitae,” Pope Paul VI’s encyclical on birth control, caused many Catholics to say publicly for the first time that they did not support one of the Church’s official teachings. Numbers of priests, sisters, and seminarians declined dramatically. More foreign-born priests began ministering in this country. Collective pastoral letters from the US bishops were more openly challenged by some Catholics.

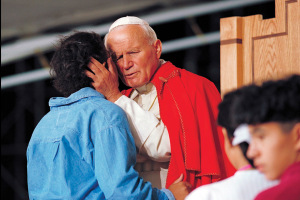

Pope John Paul II embraces a young woman during World Youth Day 1993. CNS/Joe Rimkus Jr.

The 1973 Roe v. Wade US Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion in most situations led to the rise of pro-life marches in Washington, DC, and elsewhere, with Catholics heavily involved. Papal visits to the United States became more common. World Youth Day was celebrated in 1993 outside Denver (August 10–15).

Many Catholic parishes became multicultural, celebrating liturgies in multiple languages that parish founders could never have anticipated. The first national Encuentro for Latino Catholics was held in 1972. Catholic migration to the South because of jobs led to new challenges of establishing parishes and finding the lay and clerical ministers they would need.

In 1970, an earlier St. Anthony Messenger special issue on conscience was released as the first book from St. Anthony Messenger Press; the other book was about the Sacrament of Penance. For our 100th anniversary issue, Dan Hurley wrote “St. Anthony Messenger: 100 Years of Good News” and produced a video history with interviews.

The magazine was increasingly sold over the phone by then. “AIDS: A Worsening Crisis Challenges Church and Society” appeared in January 1993. Starting in January 1981, the monthly “Followers of St. Francis” column featured US and international individual friars, Franciscan sisters, Poor Clares, and Secular Franciscans, and associates of Franciscan congregations.

1993–2018: World Church

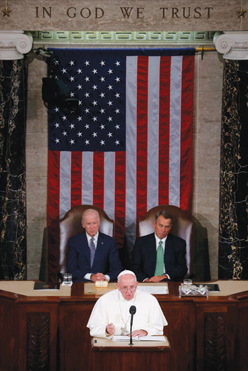

Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, the principal drafters of the Declaration of Independence, almost certainly could never have imagined that the bishop of Rome would address the US Congress in its Capitol. Pope Francis did that for 50 minutes and 40 seconds on September 24, 2015. They probably would have been very surprised to learn that this Argentinian, the son of Italian immigrants, was invited to speak by Speaker of the House John Boehner, himself a Catholic.

The pope's speech was vigorously applauded. CNS/Paul Haring

Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin would also have marveled that this pope held up Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas Merton, and Dorothy Day (two Protestants and two converts to Catholicism) as examples of all that is best in the United States: a concern for the common good; respecting the rights of all its people; openness to prayer; and caring for the hungry, the homeless, and all those people whose dignity is frequently denied.

Although in 2017, an estimated 38 percent of all US Catholics were Hispanic, they accounted for approximately 60 percent of US Catholics under the age of 18. The Internet has made us much more connected and has heightened the need for accuracy and charity in all our postings about individuals and groups.

In March 1996, some of St. Anthony Messenger became available online. Digital subscriptions for the entire magazine were introduced later. People in other countries use products from Franciscan Media such as books, audiobooks, and various online resources.

In preparation for our 125th anniversary, St. Anthony Messenger unveiled a major redesign in its January 2018 issue, introducing a new column for music reviews, bringing back recipes, and starting a “Franciscan World” column. One article that appeared in that issue was “A Pro-Life State of the Union,” by Ann M. Augherton.

Thanks!

Fr. Pat McCloskey, OFM

In 1893, Catholics often spoke of faith as an object, something that could be lost or found. In 2018, they are more likely to speak of it as a relationship, a journey with the Lord. Faith always requires knowledge (in a certain sense, an object), but that grows as the relationship grows deeper.

We take our mission statement (“To spread the Gospel in the spirit of St. Francis”) very seriously. And, despite all the changes in the world, St. Anthony Messenger magazine has remained committed to delivering the Gospel message and Catholic perspective to you, our readers of various faiths.

Thank you for 125 years of inviting us to accompany you on your faith journey!

Pat McCloskey, OFM, is Franciscan editor of St. Anthony Messenger magazine. His most recent book is Peace and Good: Through the Year with Francis of Assisi (Franciscan Media).

This article first appeared in St. Anthony Messenger magazine, May 2018

Posted in: Saint Anthony