He always puts others first

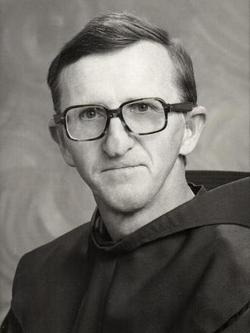

Friars Louie Lamping and Frank Jasper

Br. Louie Lamping doesn’t know that he’s remarkable. But everyone else does.

“He’s an outstanding friar,” says Frank Jasper, Louie’s guardian at St. Clement and a friend for 50 years.

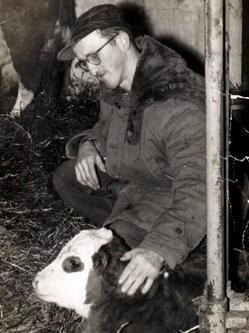

Br. Louie Lamping comforts a calf.

“He’s a hero of mine, a man to be revered,” says Fred Link, who marvels at Louie’s selflessness, his simplicity, and his capacity for hard work.

“He’s an amazing man, a very holy man,” Vince Delorenzo says of Louie, who never draws attention to himself. “I think he loves being a Franciscan.”

Just as amazing are the obstacles Louie has had to overcome. His family, poor even by Depression-era standards, survived on welfare for five years in the 1930s. Despite two operations, the cleft lip and cleft palate he was born with affected his ability to form words, leaving him with a lasting speech impediment. The ear infections he had as an infant led to a gradual loss of hearing so severe that, even with hearing aids, he is effectively deaf.

That hasn’t held him back. Since entering the Order in 1952, Louie has assumed many of the thankless but essential roles that keep things going. He almost singlehandedly ran the 160-acre farm at St. Leonard College. He juggled so many jobs at Bishop Luers High School they dubbed it “Brother Louie High School.” In recent years at St. Clement Friary he managed the books, mowed the lawn, raked leaves, shoveled snow, stocked the refrigerator and handled Mass stipends and recycling. He did it all quietly, happy to be useful, glad to stay in the background.

“He’s a very simple guy,” Frank says of Louie, a model of friar frugality. Almost everything he wears or uses comes from a thrift shop or a dollar store. “You open his closet and there’s maybe three pairs of pants and three shirts. There’s nothing, really. He doesn’t have a credit card.” Last month when Frank handed out spending money, Louie told him, ‘I don’t need any. I still have $2 left over from last month.’”

Communication

Br. Louie walking in St. Bernard.

At 90, Louie is as wiry as he was when he wrangled 1,200-pound steers at St. Leonard. Famous for long-distance walking, he still puts in at least a couple of hours a day on the sidewalks of St. Bernard. But his once-prodigious workload has all but evaporated – and “retirement” is a concept he can’t quite handle.

These days, he is seldom seen at provincial meetings or funerals. “I don’t hear anything,” is how he explains it. He will obligingly discuss his long and productive life, but communication takes time and patience on both sides. “I have nothing going on,” he says. “I’m retired, you know?”

Think about trying to talk when your mouth feels frozen in cold weather, and you understand how hard it is for Louie to enunciate. Speech therapy after his second surgery in 1971 had limited success. For this interview, subject and reporter sit side-by-side in front of a computer at St. Clement Friary, where Louie has lived since 1987. As questions typed on the keyboard flash onto the screen, he responds, sometimes verbally, sometimes with a note. Guardian Frank stops by occasionally to fill in the gaps.

It soon becomes clear that Louie’s life of service began with his family, and continued with the friars.

Br. Louie's official baby picture

Christened Wilbert, he was one of five children of Bernard and Rose Lamping. “I was born Jan. 31, 1929, in a farmhouse near Greensburg, Indiana”, with a facial disorder that left a lasting impact. “I had a hair lip [an opening in the upper lip that can extend to the nose] and a cleft palate [an opening in the roof of the mouth].” When Wilbert posed for his baby picture, the healing from cleft lip surgery at Children’s Hospital in Cincinnati was almost complete. But it would be years before surgery was done to close the cleft palate. By then, the damage to his speaking ability had been done.

Louie’s family was so poor, “Where my mom and dad lived, they never had running water,” he says. “They had my brother carry water in for laundry and cooking.” When his dad fell ill in the midst of the Depression and was unable to work, Louie did whatever needed doing around the farm. Welfare kept them afloat for five years.

As a student in Napoleon, Ind., Louie coached classmates in bookkeeping, winning first honors in a high school contest. It was a skill that stuck. “I never wanted to go to college. A dairy farmer was looking for help; I went there right after high school.” After three years of backbreaking work, “I went to St. Mary’s in Greensburg for a Sorrowful Mother Novena. There, I got the idea of being a Franciscan.”

He wrote to the Wise Man columnist at St. Anthony Messenger for advice. “It was nice of him to write back,” Louie says. “He told me I’d have a better chance of being a brother than a priest” after Louie explained, “I couldn’t speak well.” When he applied to the friars, “They saw something in me. For some reason I’m here. I always said my Guardian Angel helped me.”

Joining the friars was “quite a change in lifestyle. Besides being in a big building, I was with a lot of people.” He says they treated him well. “I didn’t have any problems. I always seem to be able to get along with people.” He was successfully trained as a tailor, mechanic, relief cook and bookbinder, working on provincial chronicles. It was as a Candidate that his hearing began to fail.

Down on the farm

Br. Louie with the Herefords at St. Leonard

In 1958, he was one of the first five friars assigned to the newly constructed St. Leonard College in Centerville, Ohio. Provincial Minister Vincent Kroger wanted to build a dairy farm for the community. Farm kid Louie knew better. “No way, not a good idea,” he told Vincent. “You need somebody milking cows twice a day,” a Herculean task. So they settled on growing crops and raising cattle for food, with Louie in charge.

The workload was staggering. He managed a herd of 98 Herefords – even assisting at birthings – and planted, cultivated and harvested 70 acres of crops. “Those cattle had to have water in the wintertime,” says Louie, who shivers at the memory of hauling hot water to the barn in freezing weather.

“The farm was self-sustaining,” says Frank, then a student at the college. “Louie didn’t put any funds into it. It produced all the beef we used at the whole school, and the sale of calves and steers when they came along would cover the cost of any equipment he would need.”

St. Leonard

It was Frank who stepped in to manage the farm when Louie finally had surgery to correct his cleft palate and was sidelined for six months. “Louie taught me how to be a farmer. He was 17 years older than I was, and none of us could keep up with him. He was one tough, tough guy.”

All those years, Louie continued to help the family back home. “His mom and dad lived in a two-room house,” according to Frank. “He would take his vacation and spend the whole two weeks splitting enough wood to get his parents through the winter.”

Louie thrived on the bustle of his next assignment at Bishop Luers High School in Fort Wayne, Ind. From 1971-’83 he ran the bookstore, handled finances and offset printing, drove buses, and did landscape work on the sprawling campus. Where did he learn landscaping? “I just did it,” he says.

Greatly admired by students,“He was a wisdom figure,” says Fred, who was principal at the time. Besides the “official” jobs, “The Dad’s Club depended on him to make Bingo happen.”

Slowing down

Br. Louie Lamping in 1978

Asked to name his favorite assignment, Louie points to St. Clement on his personnel form. Starting in 1987, “I spent 23 years here working on the books,” writing all the entries in longhand. When it was time for a computer, “I retired. I don’t like computers. I don’t even know how to use a microwave.”

Vince, who was guardian for 10 of those years, says, “Louie was a delight to live with, so giving and grateful, always concerned about others. He would say, ‘Thank you’ for the smallest thing you did.”

When Louie retired from bookkeeping, they threw him a party and had $100 bills printed bearing his likeness. Vince told him, “You did what was yours to do. Now relax and enjoy life.” For a man whose life revolves around service, that hasn’t been easy. A bit slower and less steady on his feet, he still does a few odd jobs around St. Clement, “recycling things, picking up trash, but mostly walking around,” Frank says. “He misses having something significant to do, something important.”

Br. Louie, right, at lunchtime with friars Fred Link, Michael Charron and John Flajole.

Louie will admit, “The days are long.” To fill the time he watches closed-captioned TV, especially EWTN and sports, but mostly, “I just walk,” usually after morning Mass or lunch, always for hours. In his heyday – which wasn’t that long ago – Louie could walk all the way from St. Bernard to Over-the-Rhine. He still believes his Guardian Angel is keeping him safe.

His vitality is due partly to his diet – he eats a lot of cottage cheese and never drinks alcohol – and good genes. His mom lived to be 90; his dad died one month shy of his 99th birthday. But mostly, it’s the walking. “I don’t do any other exercise.”

Deafness and the challenge of speaking are accepted facts of life. Asked if he misses hearing the music at Mass, the discussions at meetings, the talk at the dinner table, Louie responds, “I don’t worry about it; I kind of live with it. There’s nothing new about it.”

He doesn’t say much about what it means to be a friar.

He doesn’t have to.

This story first appeared in the SJB News Notes.

Learn more about our retired and infirm friars here.

Posted in: Senior Friars